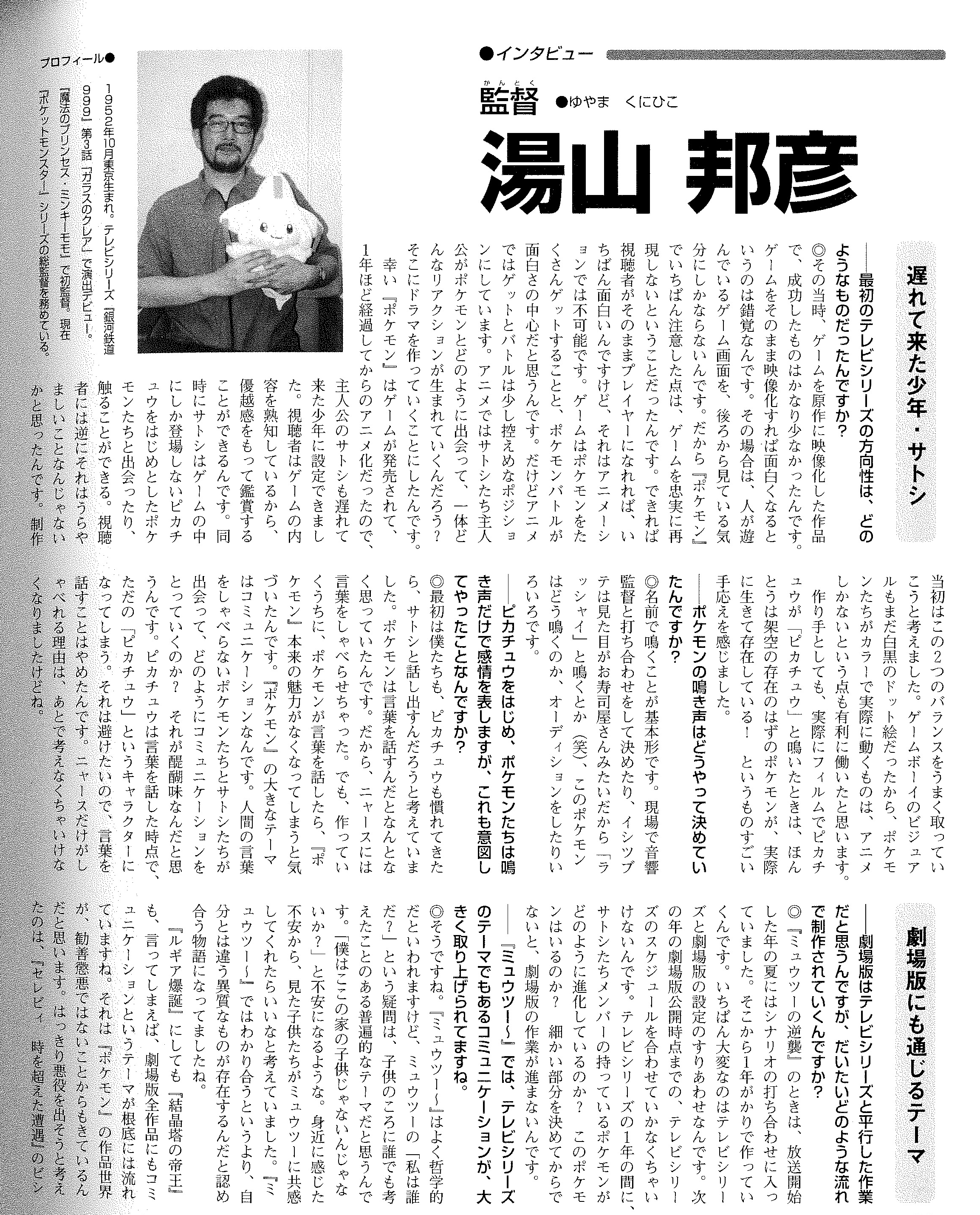

Profile: Born in Tokyo in October 1952. Made his debut as episode director with the TV series "Galaxy Express 999" episode 3, Glass Claire. He made his directorial debut with "Magical Princess Minky Momo." He is currently the chief director of the "Pocket Monsters" series.

Satoshi, the boy who came late

—What was the aim of the first TV series?

At that time, there were very few successful video game adaptations. It is a misapprehension to think that if you adapt a game directly to screen, it will be interesting. In that case, you only feel like you are looking at the game screen from behind while someone is playing it. That is why the most important thing to keep in mind with "Pokemon" was not to faithfully reproduce the game. The most interesting thing would be if the viewers could become the players themselves, but that is impossible with animation. In games, the fun is in getting as many Pokémon as possible and in Pokémon battles. In the animation, however, getting Pokémon and battles are a little more subdued. In the anime, how do Satoshi and the other protagonists meet Pokémon and what kind of reactions do they have? That's where we decided to create the drama.

Fortunately, "Pokemon" was animated about a year after the game was released, so we were able to establish the main character, Satoshi, as the boy who came late. Viewers are familiar with the game, so they can watch it with a sense of superiority. At the same time, Satoshi can meet and touch Pikachu and other Pokémon that only appear in the game. I thought that, on the contrary, viewers would be envious of this. At the beginning of production, we tried to strike a good balance between the two. The visuals for the Game Boy were still black-and-white pixels, so I think the fact that animation was the only way to actually move Pokémon in color also worked to our advantage.

As a creator, when Pikachu actually squealed "Pikachu" on film, I felt a tremendous sense of satisfaction that Pokémon, which were really supposed to be fictional, were actually alive and existing.

—How did you decide on the Pokemon's cries?

Crying with their names was the basic form. We would have meetings with the sound director on site to decide, or we would hold auditions to find out how this Pokémon would cry, such as "rasshai" for Geodude because it looks like a sushi restaurant owner (laughs).

—Pikachu and other Pokémon express their emotions only through their cries. Was this intentional?

At first, we thought that Pikachu would start talking to Satoshi when it got used to him. We thought, for good measure, that Pokemon would speak words. So we made Meowth speak. But as I was making it, I realized that if Pokémon spoke words, the original charm of "Pokémon" would be lost. The main theme of "Pokemon" is communication. How do Satoshi and others communicate with Pokémon that do not speak human language? I think that is the real thrill. Once Pikachu speaks, it becomes just another "Pikachu" character. I wanted to avoid that, so I decided it won't speak. I had to think of a reason why only Meowth could speak later, though.

Themes that can also be found in the theatrical version

—I assume the films are worked on in parallel to the TV series. What is the production process like?

For "Mewtwo Strikes Back," we started discussing the script in the summer of the year the TV series started airing. From there, we worked on it for a year. The hardest part was reconciling the traits of the TV series and the movie version. We had to match the schedule of the TV series with that of the movie version until the time of the movie's release the following year. During the one-year period of the TV series, how have the Pokémon owned by Satoshi and the other characters evolved? Is this Pokémon available? We had to decide on the details before we could proceed with the film version.

—In "Mewtwo," communication, which is also a theme of the TV series, is a big part of the story.

That's right. "Mewtwo" is often said to be philosophical, but I think Mewtwo's question, "Who am I?" is a universal theme that everyone has thought about when they were children. It is a kind of anxiety that makes you think, "Maybe I am not a child of this family." I was hoping that children who saw the film would be able to relate to Mewtwo because of the anxiety they felt close to home. In "Mewtwo," it was not so much a story of understanding each other as it was a story of accepting the existence of something different from oneself.

The theme of communication is also at the root of "Revelation Lugia," "Emperor of the Crystal Tower," and all the movies of the Pokemon series. I think this comes from the fact that the world of "Pokemon" is not one of good triumphing over evil. The only time I thought of having a clear villain was in "Celebi: A Timeless Encounter" with Vicious. The usual villains are the Team Rocket, after all (laughs). It's a world where no one gets hurt and no one dies, so naturally the climax of the story would be concentrated on communicating with the other party.

Digital images are also evolving

—I think Pokémon is also in sync with the digitalization of animation, although I think this is more the case after the second film.

Yes, that's true. "Mewtwo" has less than 10% of digital scenes. The fact that the title of the film was the only part in 3D was more for demonstration purposes. It wasn't until the second or third film that the number of digital scenes increased. Around the time of "Revelation Lugia" and "Emperor of the Crystal Tower," digital images were still rare, so images that were clearly CG allured the audience. On the other hand, digital images that blended well with the scenes were preferred from "Celebi" onward. In "Celebi," it was not yet possible to express the mood of a live-action film, but after "Guardian Spirits of the Capital of Water," we were finally able to do so in "Wishing Star of the Seven Nights."

—The settings for the movies have always been very elaborate, haven't they? I heard that you went to Venice for "Capital of Water." How was it?

I went to Venice for "Capital of Water," which is why I was able to develop such great mental images. I knew from the beginning that I wanted to set it in a city on the water. You can't see them, but there are mysterious Pokémon right next to you. Venice is a city where you really feel like there is a different space right next to you.

This time, I did not go location-hunting. Inspired by Jirachi's somewhat oriental design, Fauns was modeled after Wulingyuan in China.

The road movie-like "Wishing Star of the Seven Nights"

—Did you build the story of your latest film from the guest Pokémon as well?

The story is based on Jirachi's trait in which it sleeps for 1,000 years and awakens only for seven days. Also, since this is the first phase of Advanced Generation, I wanted to feature Masato and Haruka. Masato does not have a Pokémon yet, so he meets Jirachi, they become partners, and eventually they part ways. I decided to depict the friendship between Masato and Jirachi as the core of the story. This is why the focus this time is on Masato rather than Satoshi, the main character.

I chose a comet that comes to this planet in a thousand-year cycle as the common denominator between seven days, which can be experienced by humans, and a thousand years, which is an unimaginable length of time. The energy that Jirachi gets from the comet and gives to the earth over a thousand years is inspired by cicada larvae and other insects. The expression of Meta Groudon's abdomen was also inspired by the earth and represents magma, an energy deeply connected to the earth.

Satoshi and his friends are on a journey, but in most of the previous movies, the story had been limited to a single location. This time, I wanted to do something like a road movie, sending Jirachi back to Fauns.

—What did you aim for in terms of visuals?

For this film, I tried to show the original appeal of animation, which is the movement and timing of the images. We added digital processing to the fun of drawings. Because of this aim for interesting movement, I asked Higuchi Shinji, who worked on the Heisei "Gamera" series, to storyboard the events leading up to Meta Groudon's appearance and defeat. When I asked Higuchi, Meta Groudon ended up being larger than I had expected, but of course, a monster has to be huge to be powerful in a monster story. If you are looking for interesting movement, Meta Groudon's tentacles are a good example. Tentacles are a traditional art in animation, after all. It requires a good sense of timing for the movements, but thanks to the excellent staff, we were able to create very pleasing scenes.

—Pokemon has become a globally acclaimed work. How do you, the director, feel about it?

At first I thought I would be able to continue for about three years. Now, it's already twice that. This is the first time for me to direct a series that has lasted this long.

I think I am able to continue making it because of the accumulation of the movies and TV series, and also because of the various digital and other visual expression techniques I have cultivated over the years. It's not a Pokémon, but I feel that the series itself continues to evolve.

—So the next film will depict another new communication?

That's right. I think that the next film will depict the most difficult communication yet. Please look forward to it.